DER HELFER

AUS DEM NICHTS

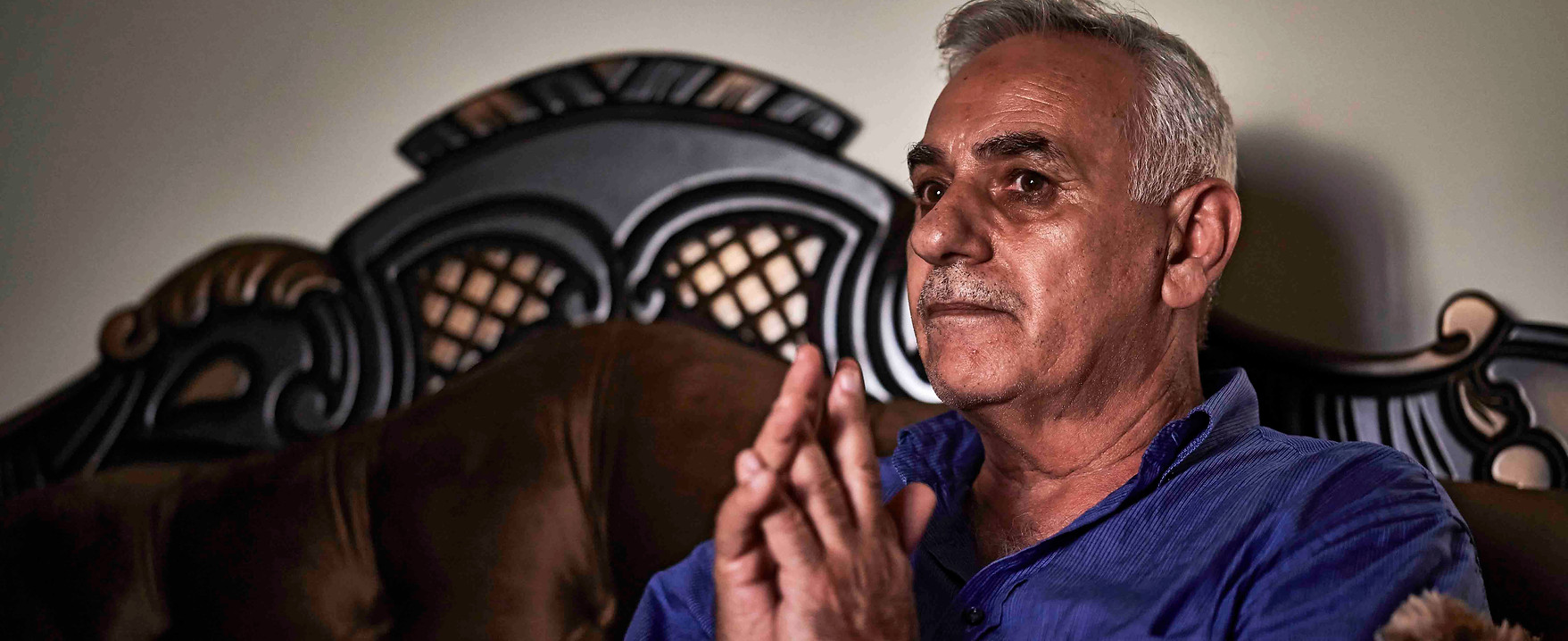

Der Krieg vertrieb Mohammed Khamis 2012 aus seiner syrischen Heimat.

In Beirut gründete er eine NGO, um anderen Geflüchteten beizustehen. Doch wie findet man Sinn in einem entwurzelten Leben?

„Man kann

– Mohammed Khamis

überall etwas leisten”

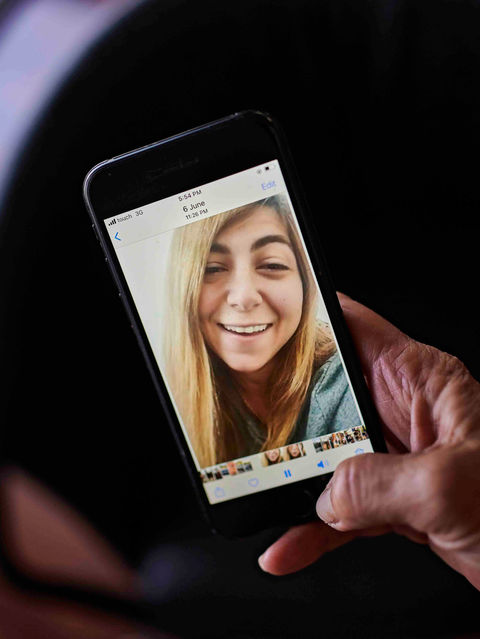

Es sind die Nachrichten auf seinem Handy, die Mohammed Khamis zeigen, was aus ihm hätte werden können. Einige seiner alten Freunde aus Maarat an-Numan in der syrischen Provinz Idlib hat er noch immer darin gespeichert, regelmäßig schreiben sie einander. Da ist Raschwan, der im schwedischen Exil zum Fußballprofi wurde. Ismail, der Bilder aus Norddeutschland schickt: Shisharauch vor weitem Himmel. Abdul, der sich in der Heimat vor den Häschern des Regimes versteckt. Da ist Faris, der zur Armee von Baschar al-Assad eingezogen wurde und nun auf seine Landsleute schießt. Die Namen der Freunde wurden für diesen Text geändert, ihre bleibende Verbindung könnte einzelne von ihnen früher oder später gefährden.

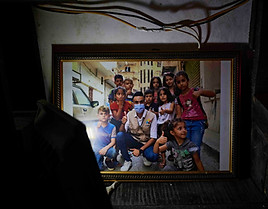

„Man kann überall etwas leisten“, sagt Mohammed Khamis und klopft mit den Fingern seiner linken Hand auf den Glastisch im Center, das er vor zwei Jahren eingerichtet hat, um anderen Menschen zu helfen. Die NGO „Hemet Shabab“ ist in einem ehemaligen Bekleidungsgeschäft im Stadtteil Bourj Hammoud untergebracht. Die Wände sind mit Holzbrettern abgestützt, vom Erdgeschoss gehen ein paar Stufen hinunter in einen fensterlosen, mit kaltem Neonlicht beleuchteten Keller. Auf einem Regal stehen gerahmte Fotos der Teams: mit lachenden Kindern, bei der Übergabe von Lebensmittelboxen an Familien, mit Besen und Schaufeln, beim großen Aufräumen nach dem 4. August 2020.

Mohammed Khamis ist der Kopf der Hilfsorganisation „Hemet Shabab“, er organisiert, schreibt, packt Tüten mit Hygieneartikeln für die Bedürftigen – und ist ein Held für die Kinder aus der Nachbarschaft

170 Freiwillige arbeiten heute bei „Hemet Shabab“. 80 Prozent von ihnen kommen aus Syrien, die übrigen sind vor allem Palästinenser, aber es stoßen auch immer mehr Libanesen dazu. „Wir wollten zeigen, dass junge Syrer etwas leisten können, auch wenn sie in diesem Land keine Arbeit finden“, sagt Mohammed Khamis. „Hemet“ bedeutet „Eifer“ oder „Ambition“, „Shabab“ ist die „Jugend“. Der 26-jährige Gründer – dürre Figur, akkurate Frisur, ständig in Bewegung – ist bis heute Fixpunkt der Organisation. Die anderen Freiwilligen nennen ihn „Mudir“, was auf Arabisch „Manager“ oder „Chef“ bedeutet. Auf die Idee, eine Art Agentur für Hilfsleistungen zu gründen – kostenlos, versteht sich –, kam Mohammed Khamis, als ihn immer häufiger andere syrische Geflüchtete nach Lebensmitteln, Medikamenten oder Ansprechpartnern bei den großen Hilfsorganisationen fragten. Er selbst hatte seit über fünf Jahren Fortbildungen bei anderen NGOs absolviert, seine Kontakte hatten sich herumgesprochen.

Am 10. September 2012 stieg Mohammed Khamis am Beiruter Busbahnhof aus einem klapprigen Gefährt. In der Nacht zuvor hatte ihm sein Vater Abd al-Sitar eröffnet, dass er ihn fortschicken werde. „Es war zwei Tage vor meinem Geburtstag, doch er ließ nicht mit sich reden, ich sollte sofort gehen“, erinnert sich Khamis. Seine Heimatstadt Maarat an-Numan im Nordwesten Syriens wurde da schon seit Wochen vom Assad-Regime bombardiert, berichtet Khamis. Er, der älteste Sohn, eines von sieben Geschwistern, stieg in ein Sammeltaxi. Zunächst für ein paar Monate, so dachte er noch, würde er bei der Familie seiner Schwester wohnen, die bereits einige Jahre zuvor in einen Beiruter Vorort gezogen war, und dann zurückkehren.

Die Zentrale von „Hemet Shabab“ liegt im Souterrain eines ehemaligen Bekleidungsgeschäfts.

Yusra Nawasra (Mitte) stammt aus Dara’a in Syrien und ist seit dem Sommer 2020 bei der Hilfsorganisation aktiv, die für viele Geflüchtete zu einem wichtigen Anlaufpunkt geworden ist

„Das Gefühl, anderen zu helfen,

– Sozdar Ahmed

hilft mir”

Vieles habe er verdrängt, sagt Mohammed Khamis, während er von seinen Jahren in Syrien und den Anfängen im Libanon berichtet. Aber er weiß noch, dass das Leben in Maarat an-Numan gut war, das Leben vor dem Bürgerkrieg: „Es gab Geld, wir hatten Arbeit und Sicherheit.“ Seinem Vater gehörten zwei Busse, im Garten standen Olivenbäume. Er war 17 Jahre alt, als sein neues Leben in Beirut begann. Er wohnte bei seiner Schwester, er schlief auf einer Couch. Nach ein paar Tagen suchte er sich einen Job in einer Möbelfabrik, monatelang schmirgelte und polierte er Küchenschränke. Mit den 2500 Dollar, die er dabei insgesamt verdiente, mietete er eine Drei-Zimmer-Wohnung, die er auch noch einrichten konnte. Im Mai 2013 kamen seine Eltern und die beiden jüngeren Geschwister nach Beirut; zuvor waren sie dem Tod nur knapp entronnen.

„Dass Mohammed anderen Menschen hilft, erlaubt mir, weiter erhobenen Hauptes durchs Leben zu gehen“, sagt sein Vater Abd al-Sitar Khamis. Der sonst so gesprächige Mohammed schweigt, nickt bloß immer wieder. „Wir waren glücklich in Syrien“, sagt der Vater, „ich wollte nicht hierher.“ Dann zeigt er auf seinem Telefon ein Foto seines Busses: ein ausgebranntes Gerippe. Er weiß nicht, wer das Fahrzeug bombardiert und den Fahrer getötet hat. Der zweite Bus wurde später gestohlen. Abd al-Sitar Khamis, 62 Jahre alt, klingt eher ratlos als verbittert, wenn er klagt: „Ich habe diese Firma 40 Jahre lang aufgebaut – was soll ich nun machen?“ Nach der Ankunft im Libanon hatte er, ermutigt vom Tatendrang seines Sohnes, neu angefangen. Er eröffnete einen Ein-Dollar-Shop. Das Geschäft ging anfangs gut, bald kam ein zweiter dazu. Aber auch das ist nun schon lange her. Heute hat Abd al-Sitar Khamis noch einen kleinen Secondhandshop, leider ein Zuschussgeschäft. Mohammed arbeitet in Teilzeit bei der Hilfsorganisation Care, sein Einkommen von umgerechnet 320 Dollar bezahlt die Mieten beider Wohnungen, des NGO-Centers und des Ladens seines Vaters.

erlaubt mir, weiter erhobenen Hauptes

– Abd al-Sitar Khamis

durchs Leben zu gehen”

„Dass Mohammed anderen Menschen hilft

Leicht war es auch schon vor der jüngsten Krise nicht. Ahmed, der 18-jährige Bruder, berichtet von täglichem Rassismus. Von anderen Jugendlichen, die seinen syrischen Akzent nachäfften, von Libanesen, die verächtlich fragten: „Was wollt ihr eigentlich hier?“ Das weiß die Familie manchmal selbst nicht. „Ach, könnten sie doch einfach wieder in die Heimat fahren“, sagt der Vater seufzend, um gleich das größte Hindernis zu nennen: „Dann müssten meine Söhne zum Militär.“ Wie für Millionen anderer syrischer Männer ist die Rückkehr vor allem deshalb unmöglich. Das UN-Flüchtlingshilfswerk hat bis 2015 etwa 860.000 syrische Flüchtlinge im Libanon registriert, schätzt ihre reale Zahl aber mittlerweile knapp doppelt so hoch. Etwa 90 Prozent davon leben zurzeit in extremer Armut, 2019 waren es „nur“ 50 Prozent. Der libanesische Staat zahlte im Jahr 2020 immerhin noch 238.000 syrischen Flüchtlingsfamilien finanzielle Hilfen. Doch die Furcht vor der Abschiebung bleibt.

Einen Tag später steht im Keller von „Hemet Shabab“ ein Software-Kurs auf dem Lehrplan. Der Unterricht hilft den Freiwilligen, sich bei anderen NGOs zu bewerben, vielleicht auch dabei, einmal einen richtigen Job zu bekommen. Oder in einem anderen Land anzukommen. Davon träumt auch Sozdar Ahmed. Die Kurdin stammt aus dem Norden Syriens, schon vor dem Krieg zog ihre Familie nach Beirut, auf der Suche nach Arbeit. Drei ihrer Brüder sind nach Deutschland geflüchtet, sie leben nun in Bremen. Sozdar selbst lebt mit ihren Eltern und zwei behinderten Brüdern in einer kleinen Wohnung in Bourj Hammoud. „Alles bleibt an mir hängen“, klagt sie. Sie muss mit dem Wohnungsbesitzer reden, dem sie nun schon mehrere Mieten schulden. Sie versucht, Medikamente aufzutreiben für die kranken Eltern und Brüder. Sie ist die Einzige, die etwas Geld verdient durch ihre Arbeit bei der Caritas. „In Deutschland könnte den beiden geholfen werden, darüber reden wir ständig“, sagt Sozdar Ahmed. In Beirut sind die Ahmeds einstweilen auf ihr kleines Einkommen angewiesen, vor allem aber auf Lebensmittelhilfen des UN-Flüchtlingswerks, dazu kommen kleine Spenden der Brüder aus Bremen. „Das Gefühl, anderen zu helfen, hilft mir“, sagt die 26-Jährige über ihren Einsatz bei „Hemet Shabab“. So geht es allen hier: Der Dank anderer Menschen gibt ihrem Leben einen Sinn.

Beim Wiedersehen im Hafenviertel ein Jahr nach der Aufräumaktion von „Hemet Shabab“ wird anhand von Handybildern verglichen, wie es hier direkt nach der Katastrophe aussah – und mit Anwohnern debattiert, wie es weitergeht. Hilfe für alle – im Hauptquartier der kleinen NGO finden auch regelmäßig Computerkurse statt

Das Aufräumen nach dem 4. August hatte für alle einen unmittelbaren Nutzen, deshalb war es so erfüllend. Auf den Straßen von Bourj Hammoud schrillten die Alarmanlagen der Autos, Kinder schrien. „Ich dachte zuerst, ein Gastank wäre explodiert“, sagt Mohammed, „oder dass ein Kampfjet angegriffen hätte – es hat gedauert, bis ich verstand, was passiert ist.“ Seine Eltern fand Mohammed unverletzt, auch sein Bruder hatte nichts abbekommen.

In der Nacht informierten die Freiwilligen möglichst viele Menschen im Viertel darüber, wo ihre Angehörigen waren. Am nächsten Morgen schrieb Mohammed Khamis bei Facebook: „Wir gehen jetzt den Menschen beistehen, die es am schwersten haben. Wir treffen uns am Märtyrer-Platz.“ 20 Tage war die Truppe von „Hemet Shabab“, ausgerüstet mit Besen, Schaufeln und Mülltüten, in den Vierteln am Hafen unterwegs, dann gingen sie zurück nach Bourj Hammoud.

- Thore Schröder

DIE LIEBE LEBT

JETZT ANDERSWO

Mit seinem kleinen Krämerladen versorgt Vasken Dschebidelikian die Nachbarschaft mit Obst und Gemüse. Seine Frau blieb nach dem 4. August 2020 bei den Kindern in Sydney. Warum ist er noch in Beirut, was hält ihn?

wäre alles noch schlimmer”

– Vasken Dschebidelikian

„Wenn Gott nicht wäre,

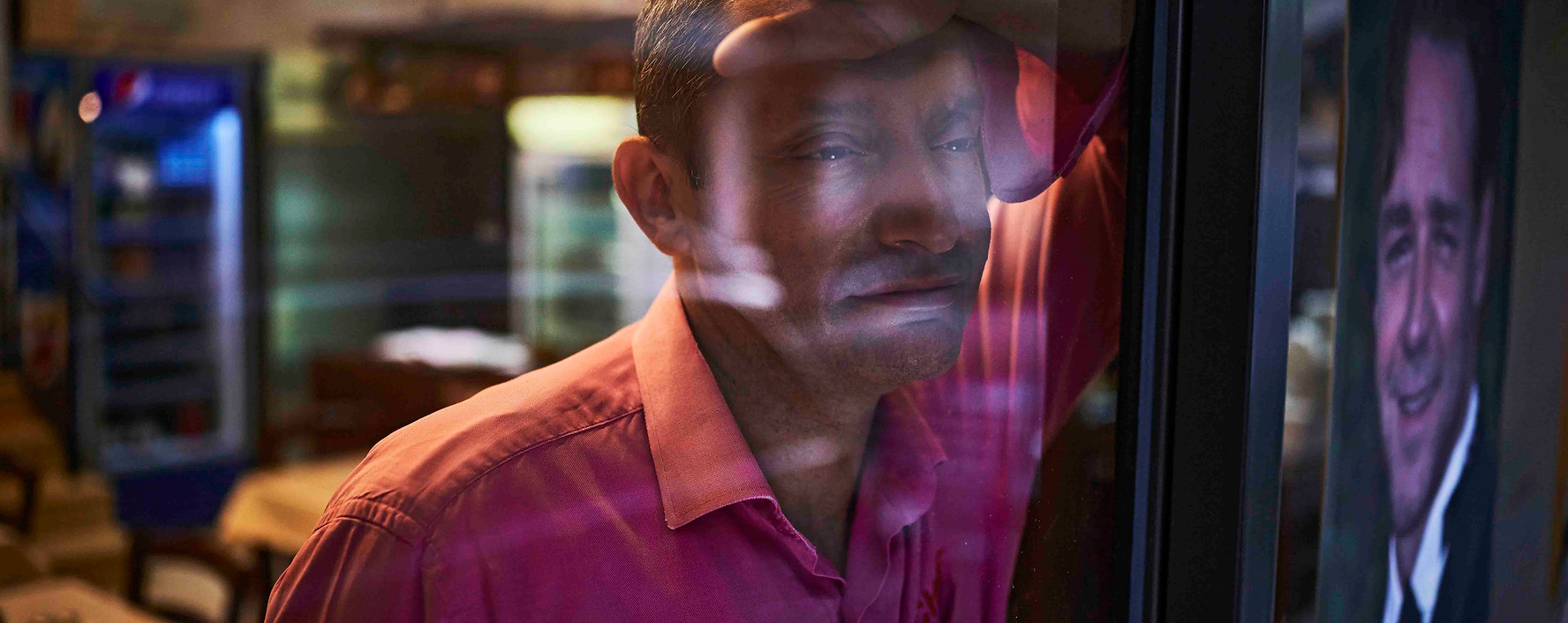

In den wenigen Stunden, die Vasken Dschebidelikian nicht in seinem Laden ist, versucht er beim Fernsehen zu entspannen

Bald nach der Explosion, als das Nötigste repariert oder ersetzt war, hat sich Vasken Dschebidelikian einen neuen Fernseher angeschafft. Ein Röhrenmodell, Marke Panasonic. Es steht nun oben auf dem Kühlschrank neben dem Eingang. Das Bild ist meist körnig, der Ton rauscht. Am Nachmittag, wenn wenig los ist, schaut er ägyptische Schwarz-Weiß-Filme aus den 1950er-Jahren.

Harmloser Klamauk und Romantik. Dann wirkt Vasken Dschebidelikian ganz entspannt. Es gibt nicht viele solcher Momente, seit Jahren schon nicht mehr, und seit dem 4. August 2020 sind sie noch seltener geworden.

Das kleine Geschäft ist ein wichtiger Anlaufpunkt im Stadtteil Geitawi;

abends blättert Dschebidelikian oft wehmütig in der Sammlung alter Familienfotos

Dschebidelikian ist Armenier. Sein Großvater Ohannes war ein reicher Tuchhändler im osmanischen Adana. Als Mitglied der armenischen Minderheit wurde seine Familie 1915 in die ostsyrische Wüste deportiert, Vasken Dschebidelikians Großmutter und zwei ihrer Kinder verhungerten. Der Rest der Familie rettete sich in den Libanon, damals französisches Mandatsgebiet. Die Eltern mieteten 1945 im Beiruter Viertel Geitawi eine Wohnung im ersten Stock eines gerade gebauten Hauses. Ihr Sohn lebt noch immer dort, direkt gegenüber liegt sein Laden. Sie sind typisch für die alten Beiruter Stadtviertel: kleine Geschäfte, die allerlei Waren des täglichen Bedarfs führen. Vier solcher Läden finden sich im Umkreis von 50 Meter, alle locken mit einer Spezialität. In „Vaskens Laden“ sind es täglich frisches Obst und Gemüse. Dschebidelikian trägt seine blau gerahmte Brille auf der Nasenspitze und meist ein Hemd, das an irgendeiner Stelle notdürftig geflickt ist. Seine Hose wird von Hosenträgern gehalten. Von früh bis spät sitzt er auf seinem Bürostuhl und nimmt telefonisch Bestellungen entgegen, die er in armenischer Schrift auf zerrissene Zigarettenstangenkartons kritzelt und dann seinem Gehilfen Abdo zuruft. „Abdo, bring 10.000 Lira Wechselgeld zu Madame Halabi.“ „Abdo, räum den Kühlschrank auf.“ „Abdo, wasch den Salat.“ So geht es den ganzen Tag.

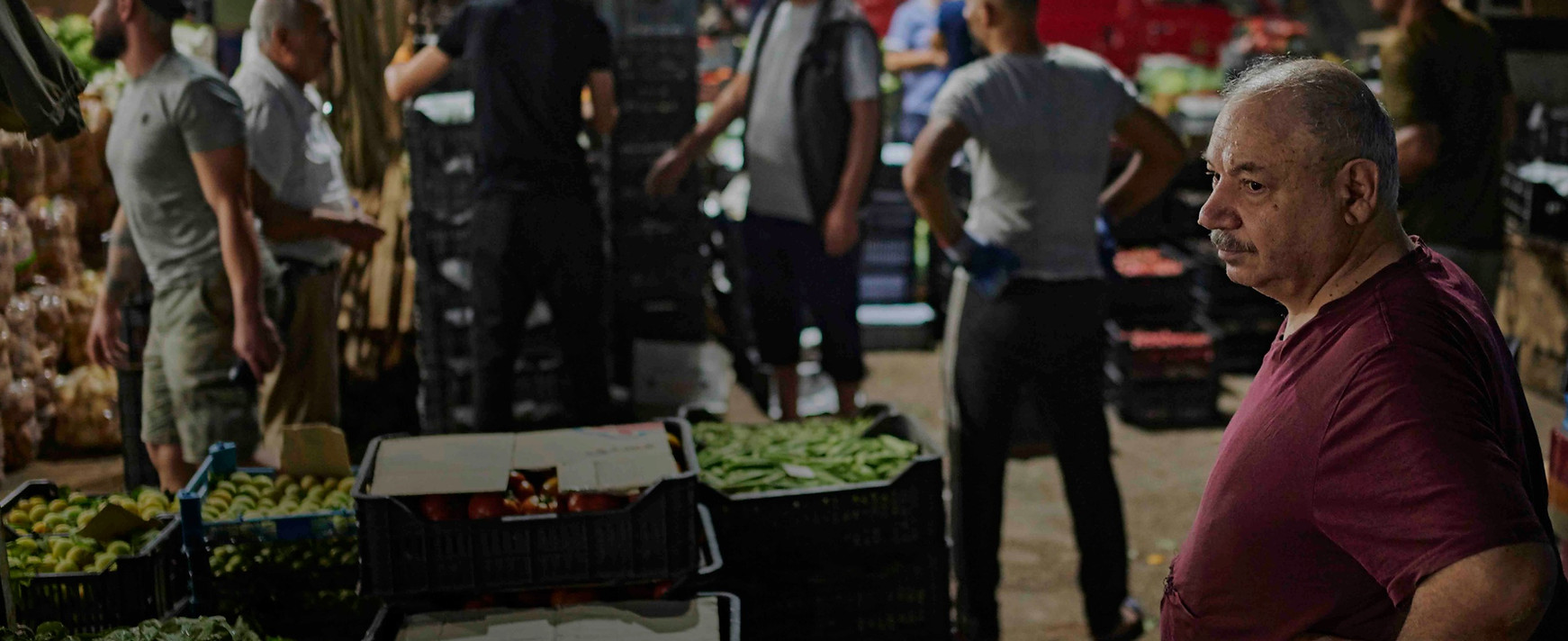

Im Innern des Ladens, der vielleicht 70 Quadratmeter misst, herrscht geordnetes Chaos. Eimer voller Mehl, Zucker, Oliven. Große Kühlschränke mit Milchprodukten, Bier und Softdrinks. Hygieneartikel, Putzmittel, frisch gemahlener Kaffee, Konserven. Ein breites Sortiment, schmale Gänge, über allem wachen Heiligenbilder. Die Preislisten hat Dschebidelikian an eine Kühltruhe geklebt. Er muss sie ständig verändern, wegen der Inflation. Zwei der großen Rollläden sind seit der Explosion dauerhaft hochgezogen. 400 Dollar würde ihre Reparatur kosten, die hat er nicht. Vasken Dschebidelikian nimmt Mittel gegen Bluthochdruck und Diabetes, sein Rücken ist schon seit Jahren kaputt. Nach wenigen Minuten auf den Beinen muss er sich wieder setzen. „Mir geht es nicht gut“, sagt er. Vor Kurzem ist er von der Leiter gefallen. Zwei Sehnen in der Schulter hat er sich gerissen, nun muss er auch noch operiert werden. Trotzdem steht er jeden Morgen um halb fünf auf, steuert seinen weißen Subaru-Kombi zum Gemüsegroßmarkt im Stadtteil Sin el Fil, um dort, vor dem großen Ansturm, die frischeste Ware zu bekommen.

„Ich bin

– Vasken Dschebidelikian

hier auch Psychologe”

Vasken Dschebidelikian ging nur bis zur fünften Klasse in die Schule. Es war Bürgerkrieg, er musste seinem Vater im Geschäft helfen. Bald lieferte er Obst und Gemüse aus, mit Pistole. Die trug er im Hosenbund, „wie in Texas“, sagt er und lacht, „hier waren viele Gangster unterwegs, wir mussten uns schützen.“ Dschebidelikian erzählt von der syrischen Belagerung und dem Beschuss von 1978. „Das war wie Stalingrad. Wir haben im Bunker geschlafen, gespielt und gegessen.“ Eine Rakete traf den 1968er Plymouth Valiant der Familie. Jede Generation in Beirut hat ihre Explosionen. 1986 starben die Eltern innerhalb weniger Wochen, 1992 heiratete Vasken Dschebidelikian die zwei Jahre ältere Beizar. „Das waren gute Jahre, es gab Geld und Stabilität“, erinnert er sich.

Vasken Dschebidelikian und seine Frau haben zwei Kinder großgezogen. Emmanuel ist 24, Shake, die so heißt wie ihre verstorbene Großmutter, 28 Jahre alt. Beide leben schon seit Jahren in Sydney. Erst war der Sohn zum Studium dorthin gezogen, dann ging seine Schwester hinterher. Als im Frühjahr 2020 die Pandemie begann, war ihre Mutter gerade zu Besuch in Down Under – und ist geblieben. Alle drei sind entschlossen, dauerhaft zu emigrieren. Auch Dschebidelikian will nachkommen. „Ich hoffe, Gott wird auch mich nach Sydney führen“, sagt er, aber so leise, dass es klingt, als würde er selbst nicht daran glauben.

Vasken Dschebidelikian ist Alleinherrscher in seinem kleinen Gemischtwarenreich; sein ganzer Stolz sind die beiden Kinder, die seit Jahren schon in Australien leben

war es doch auch gar nicht hier,

– Vasken Dschebidelikian

zumindest damals”

„Und so schlecht

Am 4. August 2020 wurde das gesamte fünfgeschossige Gebäude beschädigt, das Haus war einsturzgefährdet. Die Explosion hatte Türen und Fenster samt Rahmen herausgesprengt und die tragenden Wände beschädigt, quer durch die Mauern von Wohnzimmer und Küche zogen sich Risse. „Sogar die Sonne schien herein“, sagt Dschebidelikian. Dank einiger Spenden aus der Nachbarschaft und von Freunden ist seine Wohnung inzwischen wiederhergestellt. Vieles ist bei der Katastrophe abhandengekommen, doch immerhin hat er die gerahmten Fotos seiner Kinder wiedergefunden. Sie stehen auf dem Kleiderschrank neben seinem Bett: Tochter und Sohn bei ihren Abschlussfeiern in der Universität, sein ganzer Stolz. Dann kramt er in einer Schokoladendose, in der er alte Schwarz-Weiß-Fotos aufbewahrt hat: sein Großvater mit mächtigem Schnurrbart, Fez und Gamaschen. Sein Vater im Zweireiher mit Einstecktuch, als Bürger des Osmanischen Reiches. Seine Eltern bei ihrer Hochzeit, die Brautjungfern mit weißen Schleifen im Haar. Er selbst bei seiner Kommunion, noch mit vollem Haar.

Dschebidelikian bereut, nicht auch fortgegangen zu sein. Von den Jungen auf dem Gruppenfoto bei dieser Feier sei „sicher die Hälfte“ nicht mehr im Land. „Los Angeles, Lyon, Mailand“, zählt er auf, überall leben inzwischen Verwandte. Seine Schwester Maria, mittlerweile 68 Jahre alt, ist Anfang der 1990er-Jahre mit ihren drei Kindern nach Glendale in Kalifornien übersiedelt. Er aber konnte ja nicht weg: Erst waren da die kranken Eltern, der Vater saß im Rollstuhl, dann hat er geheiratet, dann kamen die Kinder. „Und so schlecht war es doch auch gar nicht hier, zumindest damals.“ Noch immer danke er Gott jeden Morgen für einen weiteren Tag. „Wenn Gott nicht wäre, wäre alles noch schlimmer“, sagt er, „dann wäre ich vielleicht von der Leiter auf meinen Kopf gestürzt und nicht bloß auf meine Schulter. Dann wäre ich jetzt vielleicht tot.“ So aber könne und müsse er weiterarbeiten, immer weiter, so lange es geht. „Heute sind die Gurken sehr frisch“, sagt er.

- Thore Schröder

DIE TRÄNEN, DIE WUT

UND DIE KRAFT

Yasmine und Fadlo Dagher, zwei Generationen aus einer Architektenfamilie, haben die „Beirut Heritage Initiative“ gegründet.

Ihre Mission: Sie wollen prächtige alte Häuser, die steinernen Zeugen der multikulturellen Stadtgeschichte, wieder aufbauen

„Häuser haben eine Seele”

– Yasmine Dagher

Als Yasmine Dagher ein

kleines Mädchen war und nachts nicht schlafen konnte,

schlich sie durch den Palast ihrer Familie. Sie ging

vorbei an der Bibliothek ihres Vaters, unter dem

Kronleuchter in der Eingangshalle hindurch in die Küche.

Manchmal kam sie auch an jenem Zimmer vorbei, in dem das

Klavier ihrer verstorbenen Urgroßmutter stand. Sie

lauschte der Musik, die aus dem Zimmer drang. Und war

sich sicher, dass es der Geist ihrer Urgroßmutter war,

der dort spielte. Heute weiß Yasmine natürlich, dass es

ihr Vater war, der dort damals nachts Schallplatten

hörte. Dennoch spürt sie noch immer die Anwesenheit

ihrer Vorfahren. „Häuser haben eine Seele“, ist sie

überzeugt.

Das Haus, in dem die Daghers schon in sechster

Generation leben, ist weit mehr als nur ein Wohnsitz. Es

ist ein Haus, das Bewohner, Betrachter und Besucher an

die Geschichte ihrer Heimat erinnert. Es bindet die

Menschen emotional an ein Land, dessen Gesellschaft sich

so schwer damit tut, eine gemeinsame Identität zu

finden. Der hellblaue Stadtpalast liegt im Beiruter

Viertel Gemmayzeh. Drei große Bögen zieren das untere

wie auch das obere Stockwerk. Kunstvoll geschwungene

Ornamente schmücken die Fenster, ein kleiner Garten

umgibt das Haus. Das Haus wird abgeschirmt von hohen

Bäumen und einer Mauer, es ist eine ruhige Oase neben

der Hauptstraße des Viertels, durch die sich

Autokolonnen schieben. Es ist eines dieser Häuser, bei

denen man sich jedes Mal, wenn man daran vorbeigeht,

wieder fragt, welche Geheimnisse sich wohl hinter den

Bogenfenstern verbergen.

Dann fegte im vergangenen

Sommer die gewaltige Druckwelle der Explosion im Hafen

durch das Viertel. Sie riss die Holzornamente heraus,

ließ Glasfenster zerbersten, verwüstete die Räume und

erschütterte das Fundament des Hauses. Jetzt liegt sein

Inneres offen, wie eine klaffende Wunde. Hunderte

solcher Häuser wurden an jenem 4. August 2020 in Beirut

zerstört. Viele dieser Wunden sind seither noch nicht

wieder geschlossen worden.

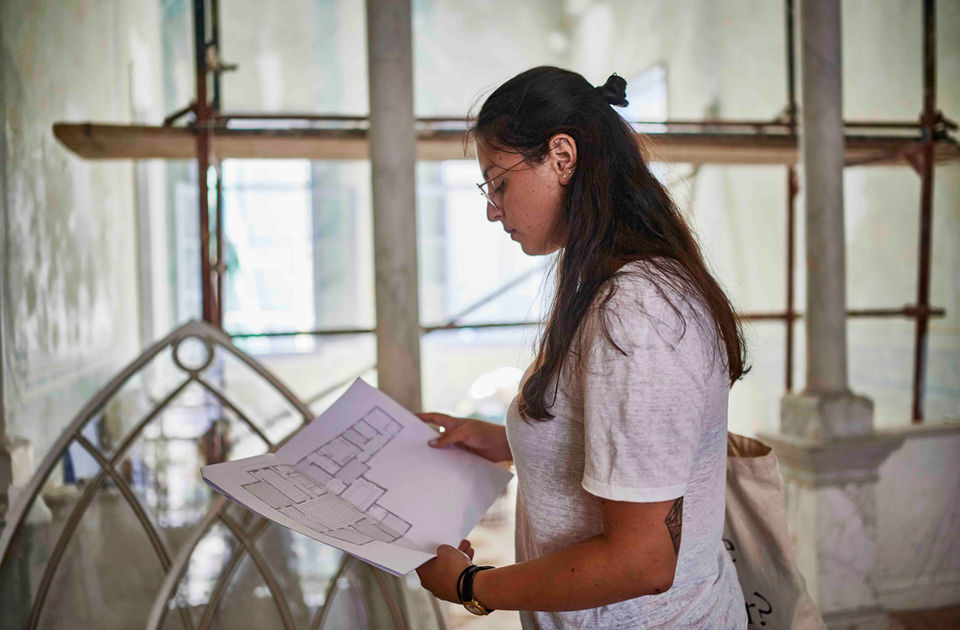

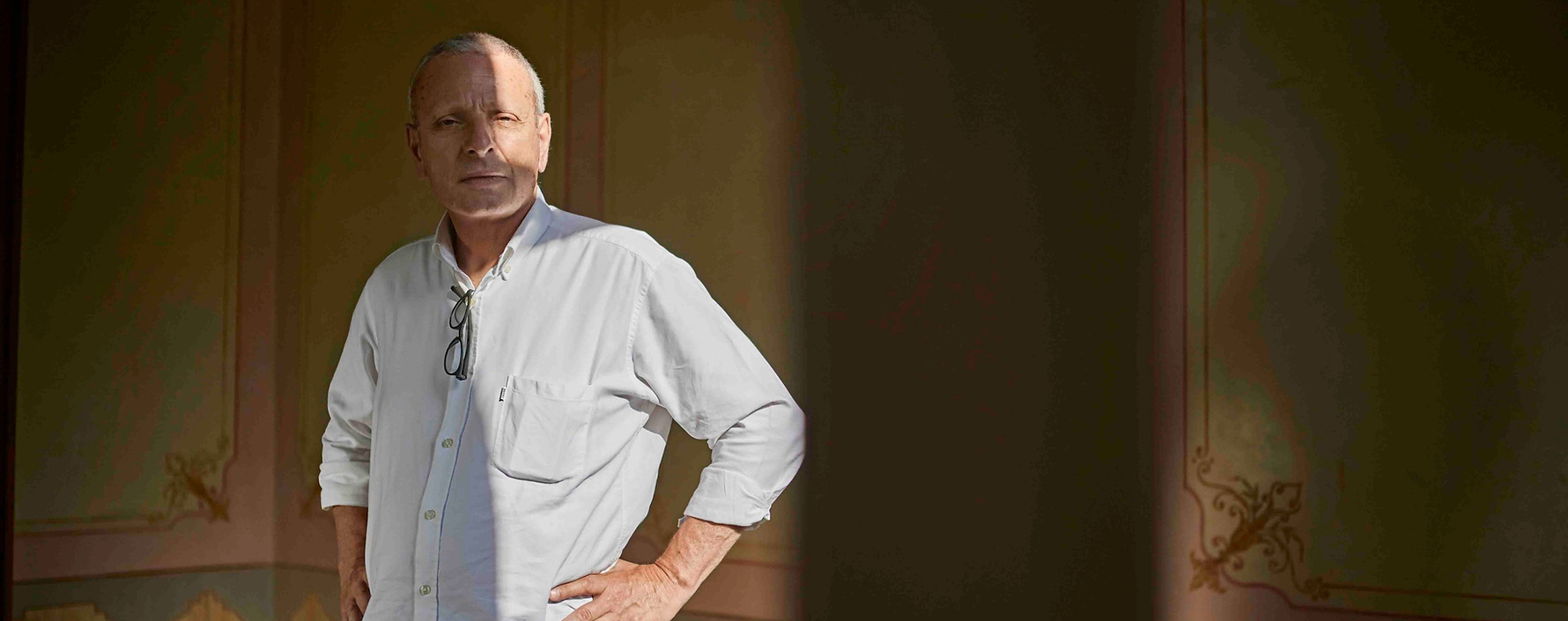

Yasmine Dagher, 27, ist Architektin. So wie ihr Vater

Fadlallah, 61 Jahre alt, der von allen nur Fadlo genannt

wird. Fadlo ist einer der berühmtesten Architekten des

Libanon. Mit seiner Firma Dagher & Hanna hat er in

den vergangenen Jahrzehnten Dutzende Projekte

realisiert. Die Explosion hat nicht nur sein Haus mit

voller Wucht getroffen. Sie hat ihn tief erschüttert.

„Ich wusste nicht, wie mir geschieht“, sagt er.

Am ersten Tag ging es nur darum zu funktionieren, sich

um seine Mutter zu kümmern, die durch die Explosion

verletzt worden war. Am zweiten Tag machten sich Fadlo

und Yasmine ein Bild vom Zustand des Hauses. Dann

schauten sie sich die übrige Nachbarschaft an. Das war

der Moment, da ihm das ganze Ausmaß der Katastrophe

bewusst wurde. „Ich habe mich hingesetzt und drei Tage

lang nur geweint“, sagt Fadlo. Fadlo ist ein ernster,

feinsinniger Mann. Wenn der Architekt über Plänen sitzt,

gleiten seine Finger über das Papier, zeichnen fast

zärtlich kleine Änderungen mit einem Rotstift ein.

Erzählt er von jenem Tag, der für viele Menschen in

Beirut der schlimmste ihres Lebens war, klingt seine

Stimme tief und ein wenig heiser, sein Blick ist von

Melancholie umwölkt. Er sitzt auf dem Sofa neben seiner

Tochter, umgeben von antiken Möbelstücken, einem Teil

seiner Geschichte, einem Teil libanesischer Geschichte.

Dann fängt er sich wieder. So wie im Sommer 2020.

doch ist es unersetzlich

für das, wofür es steht“

– Fadlo Dagher

„Das Haus selbst ist nicht wichtig,

An Tag vier dann, als er sich den Schock aus den Gliedern geschüttelt hatte, sagte sich Fadlo: Es reicht, so kann es nicht weitergehen, wir müssen etwas tun. Mit seiner Tochter und anderen Gleichgesinnten, viele davon aus dem gleichen Viertel, gründete er die „Beirut Heritage Initiative“. Ihr Ziel: die Häuser wiederaufzubauen, die Zeugnis geben vom reichen kulturellen Erbe des Libanon. Sie sammeln Spenden, bewerten den Zustand der Häuser, organisieren die Restaurierung. Die Gebäude, die es zu retten gilt, stammen aus der späten Periode des Osmanischen Reichs, der Zeit, als der Libanon französisches Mandatsgebiet war, und den Jahren der modernistischen Architektur nach der Unabhängigkeit 1943. Nach den Recherchen der „Beirut Heritage Initiative“ sind insgesamt etwa 1000 Gebäude durch die Explosion beschädigt worden, 670 davon sogenannte „Heritage Buildings“, knapp 200 von ihnen schwer. Bisher ist nur ein kleiner Teil wiederaufgebaut worden, weil die Libanesen damit auf sich allein gestellt sind. Der von Korruption zersetzte Staat hat nichts zur Aufbauhilfe beigetragen. Er hat die Bevölkerung allein gelassen, auch hier.

Die Daghers sind

prädestiniert für diese Aufgabe. Sie kennen jeden Stein,

jede Ecke des Viertels, und das seit Generationen. Ihre

Vorfahren haben sich hier in Gemmayzeh angesiedelt, als

noch Felder waren, wo sich jetzt Häuser an schmalen

Straßen drängen. Der erste Teil des Hauses wurde bereits

1820 gebaut, ein Ahn hatte dort eine Kapelle errichtet.

Damals war die Nachbarschaft voller Maulbeerbäume, aus

denen Seide gewonnen wurde, um sie nach Frankreich zu

exportieren. Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts baute Fadlos

Urgroßvater das Gebäude in ein Wohnhaus um und

errichtete das zweite Stockwerk. Zimmer für Zimmer wuchs

das Haus – und mit ihm die Familiengeschichte.

Sie ist vor allem die Geschichte eines ewigen Kampfs um

den Erhalt des Gebäudes. Ausgerechnet Fadlo Dagher, der

Mann, der Architekt, dessen Leidenschaft es ist, Dinge

zu erschaffen, hat vor allem Zerstörung kennengelernt:

1976

schlugen Gewehrkugeln der syrischen Armee in die Fassade des Hauses ein. Fadlo verputzte die Löcher.

1978

setzte eine Rakete das obere Stockwerk in Brand. Fadlo löschte das Feuer.

1981

traf eine Mörsergranate sein Haus.Fadlo beseitigte den Schutt.

1985

schlugen

fünf Granaten innerhalb weniger Sekunden ein. Fadlo

harrte

in Todesangst aus.

1989

geriet

das Haus ins Kreuzfeuer rivalisierender Milizen. Und

Fadlo tat das, was er immer tat:

Er versuchte, die Spuren des Kriegs zu tilgen.

„Wir haben alles

mitgenommen, und wir haben es jedes Mal wieder

repariert“, sagt Fadlo. Aber die Explosion im

vergangenen Sommer hat alles übertroffen, was er jemals

zuvor erlebt hat. „Wenige Sekunden haben mehr Zerstörung

angerichtet als 15 Jahre Bürgerkrieg.“ Warum er nie

daran gedacht hat zu gehen, kann er nicht sagen.

Möglichkeiten hätte es genug gegeben. Fadlos Eltern

wollten schon 1978, während einer besonders blutigen

Phase des Bürgerkriegs, die gesamte Familie außer Landes

bringen. Seine vier Geschwister zogen nach Europa, sie

sind nie zurückgekehrt. Drei Schwestern leben heute in

Paris, sein Bruder in New York. Fadlo weigerte sich

damals zu gehen. Sein Vater tobte. Seine Mutter gab

schließlich nach und blieb mit ihm in Beirut. Er weiß

nicht mehr genau, warum er unbedingt bleiben wollte.

„Jugendliche Sturheit“, vermutet er.

Doch wenn er über seine Arbeit spricht, über die alten

Häuser in seinem Viertel, seine persönliche Geschichte,

wird klar, dass mehr dahintersteckt: eine Verbundenheit

zu seinem Land, die stärker wiegt als die Angst um das

eigene Überleben, stärker auch als das eigene

Wohlbefinden. „Architektur hilft einem, die eigene

Geschichte zu verstehen“, sagt er, „die Häuser im

Libanon sind aus dem Stein gebaut, auf dem sie stehen –

beides bildet eine Einheit.“ Bei Fadlo ist es ähnlich.

Er funktioniert nur hier im Libanon, wo sich seine Ecken

und Kanten einpassen. Überall sonst auf der Welt wäre er

wohl ein Fremdkörper. Es war ein längerer Prozess, der

ihn mit dem Libanon verbunden hat. Schon sein Vater war

Architekt, als Kind hat er mit Lego gespielt, hat

Baustein auf Baustein gesetzt. Dann begann er sich mit

der Geschichte seines Hauses zu beschäftigen,

schließlich entschied er sich für ein

Architekturstudium. „Nicht wegen meines Vaters“, sagt

er, „es war eher mein bester Freund, der das auch

studiert hat – und ich hatte schlicht keine andere

Idee.“

Das Projekt, das alles

änderte, ergab sich nach dem Studium. 1985 wurde Fadlo

angefragt, ein Buch über die Geschichte des Libanon zu

illustrieren. Und zwar über die ganze Geschichte. Man

muss wissen: In der Schule werden gerade die

Bürgerkriegsjahre immer ausgespart, weil niemand

aufarbeiten will, was die Libanesen einander in dieser

Zeit angetan haben – zu heikel. Für Fadlo war diese

Auseinandersetzung mit der Geschichte seines Landes

identitätsstiftend. „Das hat mir die Augen geöffnet und

hat mir ein Gefühl der Zugehörigkeit gegeben. Damals

habe ich erst verstanden, wie wichtig dieses Land mit

seiner Vielfalt der Kulturen ist. Jedes Weltreich hat

hier seine Spuren hinterlassen – auch in uns.“

Die Vielfalt im Libanon beschwören sogar jene, die den

hässlicheren Teil ihrer Geschichte gern mit weißen

Flecken kaschieren. Der nostalgische Blick auf die

vergangene Blütezeit, in der das libanesische Bürgertum

genau jene Häuser baute, für die Fadlo heute kämpft. Sie

sind Zeichen der Entwicklung, des Wohlstands. „Der

Beiruter Hafen war damals die Brücke zwischen der

westlichen und der östlichen Welt“, sagt Fadlo, „Beirut

war arabisch, aber mit westlichen Einflüssen.“ Auch das

bezeugen die Gebäude. Für Fadlo sind sie das Vermächtnis

einer Zeit, als das Land offen für Einflüsse aus anderen

Welten war. Als Christen und Muslime gemeinsam Handel

mit dem Westen betrieben, Frauen zum ersten Mal die

Häuser verließen und sichtbarer Teil des öffentlichen

Lebens wurden, als das Bürgertum hochgebildet war und

ganz selbstverständlich mehrere Sprachen beherrschte.

an die nächste Generation weiterzugeben“

„Es ist meine Verantwortung,

das kulturelle Erbe

– Fadlo Dagher

Der Bürgerkrieg hat vieles

von dieser Gesellschaft zerstört, doch trifft man immer

wieder auf Beispiele dieses Brückenschlags zwischen den

Kulturen. Wenn Frauen mit den Hüften orientalischer

Bauchtänzerinnen kokettieren und sich dennoch ihre

markanten Nasen in kleine Stupsnäschen umoperieren

lassen. Wenn sie sich auf der Straße mit einer

englisch-arabisch-französischen Melange begrüßen: „Hi,

kifik, ça

va?“ Sie wollen sich nicht entscheiden, und sie mussten

es bisher auch nicht. Sie konnten in zwei Welten leben,

so wie aus den Moscheen der Gebetsruf erklingt, wenig

später gefolgt von den Glocken der benachbarten

Kirchtürme.

Daneben gibt es Widersprüche, die solche Bilder der

Gemeinsamkeit brechen, fallen Gegensätze ins Auge, die

kaum überwindbar scheinen. Ferraris rollen über

Schlaglöcher, gigantische Luxusapartments thronen über

elenden Flüchtlingslagern. Viele Libanesen gehen nur

ungern in Viertel oder Gegenden, wo Feinde aus

Bürgerkriegszeiten leben. Die Kluft zwischen Arm und

Reich, zwischen den Religionen, zwischen Gebildeten und

Ungebildeten ist ebenso groß wie die Gräben, die der

Bürgerkrieg in die Gesellschaft gerissen hat.

Das Haus von Fadlos Familie liegt nur etwa 100 Meter von der einstigen Front entfernt, noch immer eine unsichtbare Trennlinie zwischen dem Osten und dem Westen Beiruts. Während des Kriegs hatten sich viele seiner Freunde einer Miliz angeschlossen. Einige wurden getötet, da waren sie noch nicht einmal volljährig. Fadlo wollte nie zu einer Seite gehören. Nur einmal zwangen ihn Kämpfer, ihrer Einheit beizutreten. Seine Aufgabe war es, über Monate jede zweite Nacht in einem Bunker auszuharren, als Teil der Artillerie. Er sagt, dass er das Glück hatte, nie auf andere schießen zu müssen. „Nur einmal hieß es, dass ich mich auf einen Einsatz vorbereiten sollte, einen Hinterhalt. Ich fragte meinen Kameraden, worauf wir schießen sollten, und er sagte: ,Auf die Straße beim Parlament.‘ Ich entgegnete: ,Wir können nicht darauf schießen, das ist die schönste Straße Beiruts!‘ Er sagte: ,Na und, der Feind kommt!‘“ In Fadlos Magen zog sich alles zusammen. Aber er hatte Glück. Niemand kam in dieser Nacht.

Nach dem Bürgerkrieg hat

Beirut schon einmal ein Stück seiner Seele verloren.

Fadlo denkt noch oft an die Zeit davor, an seine

Kindheit: „Ich bin damals mit meiner Mutter durch den

Basar im Stadtzentrum gelaufen, ein chaotischer,

wundervoller Ort. Schmutzig war es, aber ich erinnere

mich noch immer an die Gerüche, an die Seele des Ortes.

Alle sozialen Komponenten der Stadt kamen dort zusammen,

Gemeinschaften. Das ist es, was der Krieg schon im

ersten Jahr zerstört hat. Und dann folgte die

systematische Demontage des sozialen Gefüges.“ Zuerst

die Orte, dann die Gedanken daran. Und schließlich,

perfide, schleichend, die Identität.

Ein Unternehmen namens Solidere, das zum Imperium des früheren Ministerpräsidenten Rafik al-Hariri gehörte, baute den Stadtkern wieder auf – und zerstörte dabei nahezu jede Lebendigkeit. Entstanden sind Prachtbauten, die an die alte Blütezeit erinnern sollen, in denen aber niemand wohnt. Teure Cafés, in denen niemand speist, und Geschäfte internationaler Modemarken wie Chanel und Hermès, die sich kaum jemand leisten kann. Seit Jahren schon gleicht Downtown einer Geisterstadt, in der nichts mehr duftet, kein Marktschreier seine Produkte feilbietet und keine Beirutis aller Couleur mehr flanieren. Kaum etwas verkörpert diese konsumorientierte Seelenlosigkeit so sehr wie der Uhrenturm auf der Place de L’Étoile, dem zentralen Platz der Innenstadt: Auf dem großen Zifferblatt prangt das Logo der Marke Rolex. All das geschah, bevor der Libanon in eine umfassende Wirtschaftskrise stürzte und das Militär die Straßen abriegelte, als 2019 Massenproteste gegen die korrupten politischen Führer ausbrachen und es dort immer wieder zu Krawallen kam.

Fadlo Dagher will einen

erneuten „Wiederaufbau“ nach diesem Muster um jeden

Preis verhindern. Auch an Gesetzen hat er

mitgeschrieben, die Käufer und Bauherren strengere

Vorschriften auferlegen sollten. Bis heute konnte kein

einziges davon in Kraft treten. „Ich habe jeden

einzelnen Kampf verloren“, sagt er seufzend. Und

trotzdem kann er nicht aufgeben. „Es ist meine

Verantwortung, das kulturelle Erbe an die nächste

Generation weiterzugeben. Und sie muss dann entscheiden,

wie sie damit umgeht.“ Für Fadlo markierte der

Bürgerkrieg das Ende der Unschuld seiner Generation. Das

Wissen, dass er nicht auf Menschen und nicht auf Gebäude

schießen konnte.

Für seine Tochter Yasmine war es die Explosion vom 4. August 2020, die einen Prozess verschärfte, der sich zuvor quälend langsam, aber unaufhaltsam angebahnt hatte. Noch immer herrschen die Warlords des Bürgerkriegs, seit Jahrzehnten teilen sie die Pfründen unter sich auf. Die Gleichgültigkeit gegenüber dem Elend der Bevölkerung ist grenzenlos, die Machthaber kokettieren nicht bloß mit dem Titel failed state, sie schreiben ihn fest. Fadlo sieht auch, wie sich Yasmine binnen eines Jahres von einem schüchternen Mädchen zu einer energischen jungen Frau entwickelt hat. Es umweht sie auch eine Traurigkeit, die kaum zu ihrem jugendlichen Gesicht passen will. Wenn sie durch die Straßen von Beirut geht, klingt sie wie ihr Vater. „Die Proteste vom Oktober 2019 und die Solidarität nach dem 4. August geben mir Hoffnung, dass wir die Probleme und die gesellschaftliche Teilung unserer Elterngeneration überwinden können“, sagt Yasmine. 2019 gingen die Menschen gemeinsam auf die Straße, unabhängig von Herkunft oder Religion. Auch nach der Explosion wogte eine Welle der Solidarität durch den Libanon.

sich wieder der Geschichte erinnert“

„Die Menschen haben die Häuser

– Yasmine Dagher

neu wahrgenommen,

Yasmine Dagher berichtet von

einem erstaunlichen Nebeneffekt der Katastrophe: Häuser

wie das ihrer Familie, die jahrelang hinter großen

Mauern verborgen waren, wurden als Teil des nationalen

Kulturguts entdeckt. „Die Menschen haben die Häuser neu

wahrgenommen, sich wieder der Geschichte erinnert“, sagt

sie. Aber die spontane Solidarität reicht nicht aus, es

fehlt an den Mitteln, sie zu retten. „Wir sind keine

NGO, wir sind eine Initiative“, erklärt Yasmine, „unsere

Mitarbeiter erhalten eine Kompensation, kein Gehalt.“

Die junge Generation könne viel lernen bei diesem

Projekt, glaubt sie, vor allem, Verantwortung zu

übernehmen: „Das Engagement der Zivilgesellschaft ist

das einzig Positive, was aus der Explosion entstanden

ist.“

Aber die aufkeimende Hoffnung wird wieder schwächer. Die Wirtschaftskrise hat die Menschen ans Ende ihrer Kräfte gebracht. Der Wert der Währung ist implodiert, die Preise explodieren, Strom, Medikamente und Benzin sind Mangelware. Die Politik, wenn man das Konglomerat von Warlords als solche bezeichnen kann, versperrt sich allen Reformen. Ohnmächtige Wut und der alltägliche Überlebensdruck legen sich wie eine unsichtbare Schlinge um den Hals der Menschen. Die stille Selbstbehauptung, von den Libanesen jahrzehntelang geübt, das stoische Weitermachen, auf dass nicht nur Verzweiflung bleibe, diese Überlebensstrategie bröckelt, die Verzweiflung nagt an der Widerstandskraft.

Wer Freunde und Bekannte im

Libanon nach ihren Plänen fragt, hört viel vom

Auswandern, immer mehr Menschen verlassen tatsächlich

das Land. Yasmine erzählt, dass aus ihrem Freundeskreis

nur noch drei von ursprünglich 15 im Land sind. „Die

Häuser sind Teil unserer Identität“, sagt Yasmine,

„deshalb müssen wir sie erhalten.“ Auch ihr Vater sieht

genau darin die Chance, Bindungen wiederherzustellen,

die mit der Not und der Hoffnungslosigkeit schwinden.

„In manchen der Häuser, die wir reparieren, lebt seit

Generationen dieselbe Familie. Damit verbinden sich die

Menschen mit dem Ort. Wir sind hier in einer Straße,

die die Geschichte Beiruts der letzten 150 Jahre

erzählen kann“, sagt er. „Ein verlassenes Haus ist ein

trauriges Haus. Es ist ein kurioses Phänomen, das wir

sehen. Die Gebäude, die am stärksten durch die Explosion

beschädigt wurden, waren leerstehende Häuser. Ein Haus

ist lebendig, es atmet, und wenn es niemanden hat, wenn

niemand darin lebt, dann stirbt es langsam – wie ein

Mensch.“

Es sollen nicht noch mehr Häuser sterben. „Das Haus selbst ist nicht wichtig, doch ist es unersetzlich für das, wofür es steht“, erklärt Fadlo, „es wird zum Gerüst für ein Wertesystem, eine soziale Struktur, eine Lebenseinstellung und eine nationale Identität.“ Häuser würden es den Menschen erlauben, weiter zurückzugehen, Fragen zu stellen, wissen zu wollen, wer zuvor dort gelebt hat. „Es verbindet die Menschen mit dem Ort, und man gewinnt automatisch Respekt – für seine Vorfahren, den Ort, seine Nachbarn.“ Also kämpft Fadlo weiter. Für die Seele der Häuser, die Seele der Stadt. Fadlo zitiert den berühmten Architekten Kevin Roche: „Etwas gut zu bauen ist ein Akt des Friedens.“ Man darf sich schon fragen, wer hier wen mehr wieder aufbaut. Er die Häuser, die Häuser ihn?

- Theresa Breuer

AUFERSTEHEN

IN RUINEN

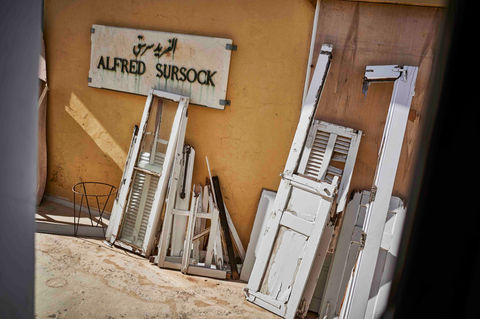

Sursock Palace, eines der Wahrzeichen der Stadt, wurde bei der Explosion am

4. August 2020 massiv beschädigt.

Beiruts berühmteste Familie kämpft seitdem um ihr Zuhause, Symbol eines vergangenen, glanzvollen Beirut

und jede Generation fügt etwas hinzu“

„Dieses Haus ist lebendig,

es lebt mit dem Erbe des Hauses,

– Roderick Sursock Cochrane

Das Chaos bekämpfen: Mary Cochrane zwischen Kisten im Sursock Palace, einem einst glanzvollen Anwesen aus dem 19 Jahrhundert. Die Explosionskatastrophe im Hafen hat den alten Beiruter Prachtbau hart getroffen

Mary Cochrane zieht eine Umzugskiste hinter sich her, vorbei an einer Wand voll leerer Bilderrahmen, quer durch das Erdgeschoss des dreistöckigen Sursock Palace. Ordnung in das Chaos bringen, darum geht es, Umzugskiste für Umzugskiste. Die Aufgabe, vor der die gebürtige Amerikanerin steht, ist gigantisch: der Wiederaufbau des Anwesens aus dem 19. Jahrhundert, das nicht nur eine Art Vorzeigeresidenz von Beirut ist, sondern auch das Heim ihrer Familie. Mary ist verheiratet mit Roderick Sursock Cochrane, dem aktuellen Vertreter dieser Dynastie. Die Sursocks sind eng mit der Geschichte Beiruts verwoben. Aus Konstantinopel stammend errang die griechisch-orthodoxe Familie durch lukrative Geschäfte und strategische Heiraten im 19. Jahrhundert beträchtlichen Reichtum und starken Einfluss.

Sie baute ein Produktions- und Vertriebsimperium auf, das sich über den gesamten Mittelmeerraum erstreckte. Auf ihrer Website heißt es: „Mit dem Aufkommen nationalistischer Regime in der Türkei und in Ägypten und der Gründung des Staates Israel verloren die Sursocks sowohl ihre Ländereien als auch ihre Produktionsstätten, und der Palast in Beirut ist eines der wenigen verbliebenen Symbole ihres früheren Ruhms.“ Das Anwesen liegt etwas oberhalb des Hafens, eine der besten Lagen der Stadt. Als die Druckwelle der Explosion durch die umliegenden Viertel fegte, wurde Sursock Palace mit voller Wucht getroffen. Kein Gemälde, kein Möbelstück blieb unversehrt, der Schaden geht in die Millionen.

Wände und Fassade der großzügigen Stadtvilla müssen mit Stahlträgern gestützt werden.

Mary Cochrane durchstreift die verwaisten Hallen und dokumentiert die zahlreichen Schäden

Im Herbst, drei Monate nach

der Explosion, muss Mary Cochrane einen Wettlauf gegen

die Zeit gewinnen. Wäre das Wasser der starken

Regenfälle, die Beirut um diese Zeit heimsuchen, einmal

in das Gemäuer eingedrungen, hätte es dessen Bausubstanz

für immer zerstören können. Die Nordfassade musste

stabilisiert, das Dach, teilweise weggerissen,

vollständig abgetragen werden. Mary Cochrane steht

mitten im Chaos. Drei Dachdecker balancieren auf

Holzplanken unter der Decke der Bibliothek, um ein fünf

mal drei Meter offenes Loch zu schließen.

Mary führt erst Vertreter von NGOs durch das Haus, spricht mit einer Gruppe italienischer Architekten, gibt den Arbeitern, die Fenster abdecken, neue Anweisungen.

Die Katastrophe beschreibt sie mit einer Sachlichkeit, als hätte sie diese nicht nur knapp überlebt, als wäre sie nicht von der Explosion rückwärts über ein Sofa geschleudert worden, dessen Lehne sie mit ihrem Arm zerbrach, als hätte sie sich nicht den Ellenbogen und mehrere Rippen gebrochen, als hätte ihre Lunge nicht punktiert werden müssen. „Okay? Sie sollten sich auch den Rest ansehen“, sagt sie, dreht sich abrupt um und geht.

nicht allein stemmen,

dazu fehlen uns die Mittel“

„Wir können das

– Mary Cochrane

Ein paar Monate später, knapp ein Jahr nach der Explosion, ist es still im Palast. Und dunkel. Die Fenster sind abgedeckt, die Kunstwerke verpackt, die Arbeiter verschwunden. Die Möbel-Skelette sind verhüllt mit Plastikplanen, die schon von einer dicken Staubschicht bedeckt sind. Die Familie befindet sich noch immer in Phase eins der Wiederaufbauarbeiten: sauber machen, organisieren, Inventur. Danach müssen die Struktur des Gebäudes gefestigt und muss das Dach richtig gedeckt werden. In Phase drei soll dann Zimmer für Zimmer renoviert werden. „Im Jahr fünf nach der Explosion dürfte von der Zerstörung im Haus endlich nichts mehr zu sehen sein“, hofft Mary Cochrane. Dann erst geht es an die Feinarbeit: Vorhänge, Bilder, Innendesign. Irgendwann soll Sursock Palace für private Touren geöffnet werden. „Wir hoffen auf Sponsoren, die je ein Zimmer renovieren oder auch nur eine Decke“, sagt Mary Cochrane, „wir können das nicht allein stemmen, dazu fehlen uns die Mittel.“

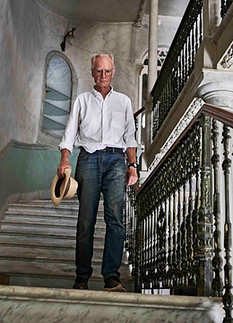

Wenige Tage nach der

Explosion stand Roderick Sursock Cochrane in seinem

zerstörten Wohnzimmer, der Flügel neben ihm mit einer

Ascheschicht bedeckt, hinter ihm zerborstene Holzbalken,

vor ihm umgestürzte Holzstühle. Ein Fotograf schoss ein

Bild, das um die Welt ging. Seine Frau Mary und seine

Mutter Lady Yvonne Cochrane Sursock befanden sich zu dem

Zeitpunkt beide auf der Intensivstation.

17 Tage später erlag seine Mutter ihren Verletzungen,

sie wurde 98 Jahre alt. Die Matriarchin war eine

Philanthropin, Kunstsammlerin, eine Berühmtheit. Sie

besaß die britische, italienische und libanesische

Staatsbürgerschaft, doch gegen Ende ihres Lebens wurde

Beirut zu ihrer größten Leidenschaft. Vor allem wollte

sie das kulturelle Erbe der Stadt bewahren, die

einzigartigen Bauten, die in der ersten Hälfte des 20.

Jahrhunderts entstanden waren. In deren Architektur

venezianische und osmanische Motive verschmolzen, die an

eine der besten Zeiten Beiruts erinnern.

Roderick Sursock Cochrane hofft, dass seine Gesundheit es ihm erlaubt, die langwierige Sanierung des Familiensitzes abzuschließen; aus ihrer wertvollen Gemäldesammlung wollen er und seine Frau Mary kein einziges Werk abgeben

dass wir am Ende noch genug Kraft haben”

„Es wird ein Marathon, wichtig ist,

– Roderick Sursock Cochrane

Schräg gegenüber vom Familienpalast liegt auch das Sursock Museum, das Lady Cochranes Onkel Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock 1912 erbauen ließ und nach seinem Tod der Stadt vermachte. Ein architektonisches Prunkstück, dessen Dauerausstellung zeitgenössische libanesische und internationale Künstler zeigt und das von 2008-2015 aufwendig renoviert worden war. Auch dort: alles zerstört, in wenigen Sekunden. Die Liebe zur Kunst ist Familientradition. Rodericks Urgroßvater Moussa Sursock baute ab 1869 den Familienpalast. Sein Sohn Alfred, Rodericks Großvater, war selbst Künstler. Er hatte einen Hang zu Italien, heiratete eine italienische Adlige und bescherte dem Familienbesitz eine Sammlung barocker Kunstwerke, die von jeder folgenden Generation erweitert wurde. „Dieses Haus ist lebendig, es lebt mit dem Erbe des Hauses“, sagt Roderick Sursock Cochrane. „Aber vor allem“, seine Stimme wird weicher, „ist es ein Zuhause.“ In den Trümmern finden sich Bilder, die das frühere, unbeschwerte Leben des Paars zeigen. Sie hat die Arme um seine Schultern geschlungen, beide mit Hut und Sonnenbrille, in eleganter Sommergarderobe, auf einem Fest.

Es sind nicht nur die Erinnerungen an bessere Zeiten, die Roderick Sursock Cochrane antreiben. Es ist auch das Pflichtbewusstsein einer alten und großen Dynastie. Lady Cochrane verkörperte das alte Beirut in seiner Blütezeit als glamouröses kulturelles Zentrum der Region. In diese Welt wurde Roderick hineingeboren. „Er hat eine fast schon religiöse Beziehung zu dem Haus, dazu ein sehr ausgeprägtes Pflichtbewusstsein“, sagt Mary. Die Sursocks sind Teil einer verschwindenden alten Welt der feingeistigen Eleganz, in der es um Kunstschätze und Galerie-Eröffnungen geht. Viele der Gebildeten reisen nun nicht mehr nur in den Urlaub nach Italien oder Frankreich, sondern verlassen das Land endgültig. Roderick dagegen will seine Welt vor dem Untergang bewahren: „Unser Kampf hier, unsere Existenz hier ist rein kulturell. Ich glaube, dass der Libanon, was auch immer geschieht, als Land bestehen bleiben wird. Aber das Gesicht des Libanon kann sich ändern. Und das ist für uns gefährlich. Wir wollen den Libanon offen für den Westen halten, offen für alle.“

Keiner der Räume von Sursock Palace ist unversehrt geblieben, manche wirken mit ihren schmerzlich sichtbaren Leerstellen beinahe wie eine ironische Kunst-Installation

und auch die Geschichte dieses Landes“

„Wenn wir beschließen, diese Kunstwerke,

die Teil der Geschichte des Hauses sind, zu verkaufen,

verwässern wir die Geschichte des Hauses

– Mary Cochrane

Dabei wäre es auch für die Sursocks einfach zu gehen. Im Zuge der Aufräumarbeiten entdeckte ein Kunsthistoriker zwei bislang unbekannte Gemälde der italienischen Barockmalerin Artemisia Gentileschi, heute sind sie mehrere Millionen Dollar wert. „Es wäre simpel für uns, aber das werden wir nicht tun“, erklärt Roderick Sursock Cochrane, „dieser Ort ist unsere Beziehung, unsere Existenz.“ Im Moment bilden Veranstaltungen im Garten des Palasts ihr Haupteinkommen. Fast jedes Wochenende findet eine Hochzeit statt, trotz der Wirtschaftskrise.

Wer Sursock Palace als Location mietet, will die ganz große Show, mit Sushi-Pyramide, gigantischen Drohnen und professioneller Filmcrew, die das alles für die Nachwelt festhält. All das ist nicht die Welt der Cochranes. Doch sie freuen sich über jeden Event. „Alles was hier passiert“, sagt Mary Cochrane und nickt Richtung Garten, „fließt direkt dorthin“, während sie auf den Palast zeigt. Dann greift sie sich eine neue Kiste. Sie muss noch aufräumen.

- Vanessa Schlesier

DAS HAUS DER

FREMDEN TRÄUME

Annie Vartivarian verlor bei der Explosionskatastrophe ihre Tochter. Seitdem setzt sie alles daran, deren größten Traum zu erfüllen: eine Mischung aus Galerie und Kunstmesse

„Gaïa hat sich entschieden zu gehen“

– Annie Vartivarian

Was bleibt, ist die Leere: Annie Vartivarian, 62, in der Beiruter Hochhauswohnung, in der ihre Tochter bei der Explosionskatastrophe tödlich verletzt wurde. Der Ground Zero der Detonation liegt nur 900 Meter entfernt

Der Blick von der Wohnung im zehnten Stock des Wohnturms Rmeil 449 am südlichen Rand des Stadtteils Aschrafiyyaa ist fantastisch. Nur sehr vereinzelt versperren höhere Häuser den Blick auf das Mittelmeer, auf die Schiffe in der Bucht von Beirut und rechts hinüber auf die Berge, deren Höhen im Winter von Schnee bedeckt sind.

Auch den Hafen mit seinen Containerbrücken sieht man gut von hier oben, man erkennt den Ort, wo am 4. August 2020 das Ammoniumnitrat explodierte. Nur rund 900 Meter sind es bis zu den Überresten von Hangar 12.

Erinnerungen an ein viel zu kurzes Leben: Annie Vartivarian inmitten von Memorabilien.

Im Alltag der trauernden Mutter ist Tochter Gaïa omnipräsent

wir haben viele Dinge gemeinsam gemacht“

– Annie Vartivarian

„Sie war wie eine Freundin;

Annie Vartivarian ist 62 Jahre alt, eine kleine Frau, 1,60 Meter vielleicht. Sie trägt die Haare kurz, spricht schnell, raucht viel. Die Ereignisse des 4. August 2020 rekapituliert sie wie einen Tatsachenbericht, nahezu ohne Gesten. Wenn man wissen möchte, wie es ihr dabei geht, sagt sie knapp: „Fragen Sie mich nicht nach meinen Gefühlen.“ Mutter und Tochter waren gerade nach Hause gekommen an diesem Dienstagabend, es war kurz nach sechs Uhr. „Gaïa wollte duschen, hatte sich schon ihr T-Shirt ausgezogen“, erinnert sich Annie Vartivarian,

„doch dann hörte sie die erste Explosion und kam zu mir ins Wohnzimmer gerannt.“ Mutter und Tochter standen an der acht Meter breiten Fensterfront und sahen den Rauch über dem Hafen aufsteigen. Während in Hangar 12 die Chemikalien explodierten, hörten die beiden Frauen schon die ersten Fenster zerbersten, die Druckwelle raste heran. „Lauf, Gaïa“, schrie Annie Vartivarian und floh in den Flur vor der Küche. Ihre Tochter kam nicht nach. Sekunden später war da nur noch Zerstörung. Das Wohnzimmer voller Scherben, Trümmer, Staub.

Einem Leben, das aus den Fugen geraten ist, geben Rituale Struktur: Annie Vartivarian besucht nahezu täglich das Grab ihrer Tochter

„Ich bin kein religiöser Mensch.

Aber ich glaube an Spiritualität.

Ich glaube, sie ist jetzt in einer anderen Dimension.

Und das respektiere ich“

– Annie Vartivarian

Gaïa Fodoulian wurde 1991 als jüngere Schwester der zwei Jahre älteren Zwillinge Mariana und Leon geboren. Sie ging in Beirut zur Schule, studierte Produktdesign in Genf und Mailand. Nach dem Studium arbeitete Gaia drei Jahre lang in der Galerie Letitia im Westen Beiruts. Annie Vartivarian ist Ko-Gründerin und Direktorin dieser Beiruter Kulturinstitution. Die Tochter betreute die Künstler – internationale, aber auch lokale Avantgardisten –, kümmerte sich um den Online-Auftritt und die Social-Media-Kanäle.

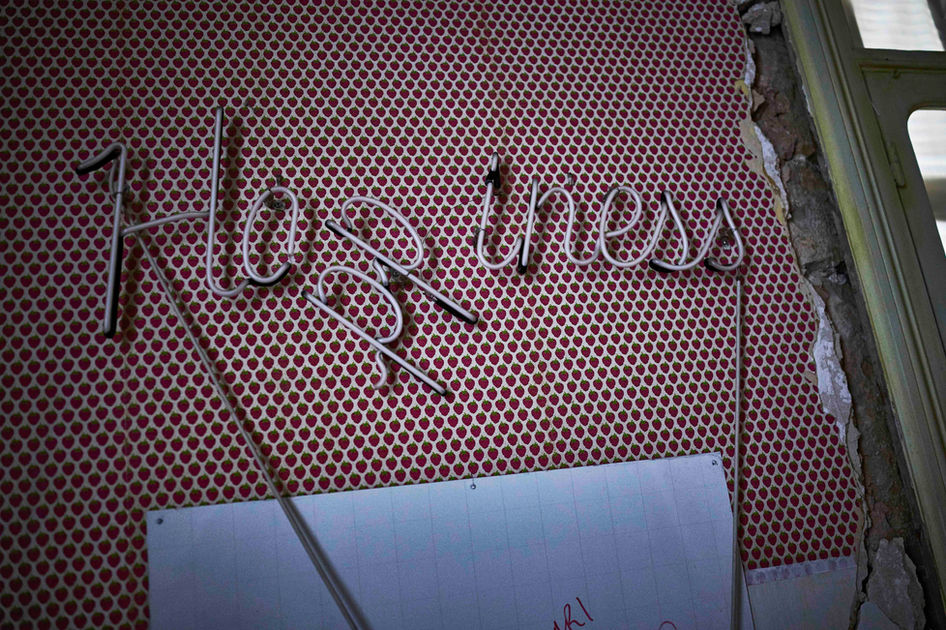

Als der gesamte Libanon in die Wirtschaftskrise stürzte und auch die Galerie ins Trudeln geriet, beschloss Gaïa im Frühjahr 2020, kurz vor der Pandemie, ein eigenes Projekt zu starten. Nicht nur wollte sie ihre Möbelentwürfe umsetzen, sie wollte auch einen größeren Rahmen schaffen für einheimische Künstler. Ihr Konzept, das sie „Art Design Lebanon“ taufte: keine stationäre Galerie, kein White Cube, sondern ein Forum für Veranstaltungen an besonderen Orten der Stadt.

könnte ich wahrscheinlich

nicht weitermachen“

„Wenn ich so denken würde wie alle,

dass die meine Tochter getötet haben,

– Annie Vartivarian

Als sich Annie Vartivarian in der zerstörten Wohnung über ihre schwer verletzte Tochter beugte, begann ihr Telefon zu klingeln. Pausenlos. Es hörte gar nicht mehr auf. Verwandte und Freunde aus aller Welt wollten wissen, was los war. Dann kam Mariana, die ältere Schwester, sie brachte zwei Helfer aus der Galerie mit. Einer der Männer nahm Gaïa auf seine Schultern, trug sie vor die Tür. Weil kein Autofahrer anhalten wollte, trug er sie immer weiter, bis zum Krankenhaus Saint George. Auch das Spital war von der Explosion verwüstet und heillos überlastet. Nach einer Stunde gelang es den Frauen, einen Notarztwagen zu organisieren.

Zwei weitere beschädigte Kliniken weigerten sich, die Patientin aufzunehmen.

Während sich das Fahrzeug mit Blaulicht und Sirenengeheul durch den Verkehr quälte, hielt die Mutter die Hand ihrer Tochter, die Schwester presste ihr ein Sauerstoffgerät auf das Gesicht. Erst in einer Klinik im Vorort Jal el-Dib ließen sich die Ärzte erweichen und nahmen Gaïa auf. Zwei Tage später wurde sie begraben. Ihre Mutter hatte ihr ein rotes Kleid herausgesucht für den letzten Weg. „Gaia hätte auf keinen Fall ein langweiliges Outfit gewollt“, sagt Annie Vartivarian. Eine Obduktion hatte es in all dem Chaos nicht gegeben, die Todesursache ist bis heute nicht geklärt. Die Mutter vermutet, dass ihre Tochter an inneren Blutungen gestorben ist. Die Druckwelle hatte sie wohl in der Wohnung mit voller Kraft erfasst.

Im Traumhaus: Annie Vartivarian in der Tabbal-Villa, einem leerstehenden Prachtbau im Nobelviertel Aschrafiyyaa. Hier startete sie „Art Design Lebanon“, das ihre Tochter Gaïa geplant hatte

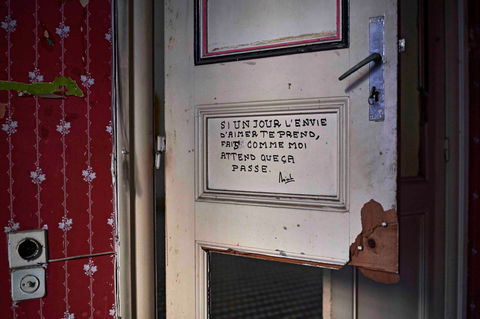

Um mit einer schrecklichen Erfahrung zu leben, so Annie Vartivarians Credo, müsse man sie mit positiver Kraft konfrontieren. Also suchte sie einen Ort für den Start von Art Design Lebanon. Der junge Architekt und Designer Samer Bou Rjeily machte Annie Vartivarian im Dezember auf die zugewucherte Villa im Nobelviertel Aschrafiyyaa aufmerksam und stellte den Kontakt zu den Besitzern her. „So einen Ort hatte sich Gaia gewünscht“, sagt die Galeristin über das Haus, ein verwunschenes Bauwerk, selbst von der Explosion schwer erschüttert: das Tabbal-Gebäude, eine Beiruter Legende.

„Hier hat sie ihre glücklichsten Jahre verlebt“, erzählt Ana Maria Téhini über ihre Mutter, die als Margo Tabbal 1925 in ebendiesem Haus geboren wurde. Margos Vater Sélim hatte einst die ersten Geschosse des Gebäudes errichtet, Margo wiederum lernte auf der Terrasse ihren künftigen Ehemann kennen. Alberto Haddad war Spross der ebenfalls vermögenden Nachbarsfamilie, deren Balkon direkt an den der Tabbals grenzte … Die beiden heirateten und bekamen fünf Kinder. Ana Maria Téhini, geborene Haddad, ist das zweitälteste.

Ihr Vater starb bereits 1968, ihre Mutter blieb danach allein. Zuletzt wohnte von der Familie nur noch Margos Bruder Georges im Tabbal-Gebäude – bis er am 4. August wegen einer Routineuntersuchung ins Saint-George-Krankenhaus kam. Seine Schwester besuchte ihn am Tag der Katastrophe. Kurz vor der Explosion trat sie an das Fenster seines Zimmers im sechsten Stock. Stunden später wurde Margos lebloser Körper in einen Vorhang gewickelt nach unten getragen.

„Es war immer ihr Wunsch, dass dieses Haus erhalten bleibt und für die Kultur geöffnet wird“, sagt die 65-jährige Tehini. Um das viergeschossige Gebäude für die Premiere von Art Design Lebanon nutzen zu können, wurden der Gummibaum und der Zitronenbaum vor der Tür beschnitten, dann tonnenweise Unrat und Trümmer herausgetragen. Georges Tabbal hatte nur das oberste Stockwerk bewohnt, der Rest der Villa stand jahrelang leer und war völlig heruntergekommen. Etwa 150.000 Dollar werden wohl benötigt, um das Haus mittelfristig zu sichern und das Leck im Dach zu flicken. Immerhin: Die Gespräche mit potenziellen Förderern laufen.

In Form gebracht: Im Hof der zugewucherten Villa stehen bunte Bänke aus Stahl. Die Entwürfe stammen von der verstorbenen Gaïa Fodoulian

Da ist eine Leere. Und in mir?

– Annie Vartivarian

„Das Haus ist wirklich leer ohne sie.

Ein weiteres großes Loch“

Art Design Lebanon, das wechselnde Ausstellungen zeigen soll, wurde im April 2021 eröffnet, nach dreimaliger pandemie-

bedingter Verschiebung. Vier Monate lang hatte Annie Vartivarian darauf hingearbeitet,

neun Künstler zeigten ihre Zeichnungen, Skulpturen, Videoinstallationen und Architekturskizzen. Im Hof stand eine der knallroten Bänke, deren Design Gaïa Fodoulian einst in Mailand entworfen hatte. Die Bildunterschrift eines Beitrags, den sie am 4. August auf Facebook gepostet hatte, knapp drei Stunden vor dem Inferno, gab der Show ihren Titel: „Jeder Mensch ist Schöpfer seines eigenen Glaubens.“

Es war eine Ausstellung wie ein frischer Wind, ein trotziges Lebenszeichen gegen den Untergang der Stadt und auch ihrer Kunstszene.

Die nimmermüde Annie Vartivarian plant schon die nächste Ausstellung und überlegt, was später einmal mit den Einnahmen geschehen soll, sollte es jemals ein Plus bei Art Design Lebanon geben. Jeden Tag zündet sie Kerzen an für ihre Tochter. So werden, sagt sie, gute Wünsche an die Verstorbenen übermittelt. Annie Vartivarian geht es um alles, um ihre Liebe, um Gaïa: „Ich möchte, dass ihre Seele glücklich wird.“

- Thore Schröder

ALLE GLEICH WILLKOMMEN

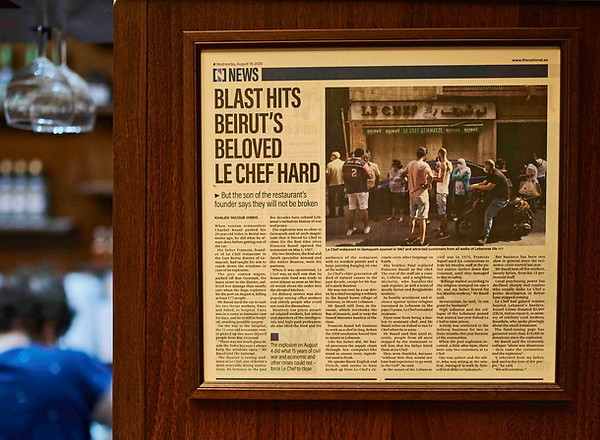

Das „Le Chef“ in Gemmayzeh ist eine Beiruter Legende, für den Wiederaufbau des Restaurants spendete auch Hollywood-Star Russell Crowe. Manche Schäden sind mit Geld nicht zu beseitigen, aber es wird weitergekocht

– Charbel Bassil

Sie sagen immer:

,Das ist der Welcome Man‘“

„Niemand nennt mich Bassil oder Le Chef.

Guter Geschmack ist Familiensache: Charbel Bassil (oben) führt ein strenges Regiment, sein Bruder Paul (unten) schwingt die Kochlöffel in der Beiruter Restaurant-Institution „Le Chef“

traditionelle libanesische Gerichte“

„Die Menschen wollen

– Charbel Bassil

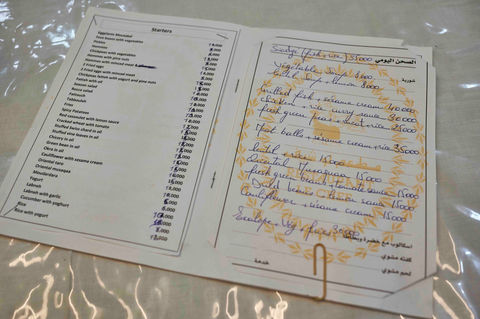

Zackig fliegen im „Le Chef“ die Bestellungen die Treppe hinauf. Und innerhalb weniger Minuten serviert Charbel Bassil das Gewünschte. „Die besten Speisen des Orients und des Okzidents zu unschlagbaren Preisen“, verkündet die Visitenkarte des Lokals im Beiruter Viertel Gemmayzeh. Darauf sind auch die Tagesgerichte vermerkt, die schon seit der Eröffnung 1967 auf der Karte stehen: gefülltes Lamm, Fischeintopf, Kibbeh – ein typisch libanesisches Röstgericht aus Weizen und Hackfleisch, das mit einer besonders krossen, zum Schluss noch mal mit Fett begossener Kruste serviert wird.

Ein Raum, neun Tische, fünf Stufen hinauf zur offenen Küche, rechts der Tresen.

Eine gastronomische Ikone, ein Leuchtturm des Quartiers, der Stadt, der Gastfreundlichkeit, auch für das Leben und Überleben in dieser Metropole.

Wer das „Le Chef“ in der Rue Gouraud betritt, wird zunächst mal: fröhlich angebrüllt. „Weelcooome …!“, begrüßt Charbel jeden Gast mit dröhnendem Bass, dabei dehnt er die Vokale, ohne eine Miene zu verziehen – Robin Williams’ legendärer Radiogruß im Hollywood-Film „Good Morning, Vietnam“ hat ihn einst dazu inspiriert. Charbels Willkommen – das er bei offenkundig ausländischen Besuchern um „… to Lebanooon!“ ergänzt – ist eines der Markenzeichen des Restaurants.

Seit mehr als 50 Jahren punktet das Restaurant mit guter libanesischer Hausmannskost. „Le Chef“ liegt im Stadtteil Gemmayzeh, umliegende Straßen zeigen Spuren der Explosionskatastrophe

Die Bassils stammen aus dem Örtchen Daraoun, nördlich von Beirut über der Bucht von Dschounieh gelegen. Von dort zog Charbels Vater François einst in die Welt, kochte in Riad, dann in Bagdad, 1958 kam er zurück in seine libanesische Heimat. In Beirut verdingte er sich in allerlei Lokalen, ehe er 1967 mit seinen Brüdern Antoine und Boutros das Restaurant eröffnete, im damals noch verschlafenen christlichen Wohnviertel Gemmayzeh, ganz in der Nähe der malerischen Saint-Nicolas-Treppe. François Bassil, der nicht nur Wirt, sondern vor allen Dingen Koch war, wählte den Namen:

„Le Chef“.

Die Leidenschaft für das Lokal eint die Familie bis heute. 2013 übernahm Charbels sechs Jahre älterer Bruder Paul, heute 58, das Regiment in der Küche. Kommt die Sprache auf den Vater, werden die beiden Brüder aufgeregt laut, das Andenken an den Vater ist den beiden so heilig wie sonst nur ihr Glaube. Beide tragen Rosenkranzketten, Paul unter dem weißen Kochkittel, Charbel unter seinem rosa Hemd, über dessen Brusttasche der Name des Restaurants eingestickt ist. Die Brüder führen das Lokal mit ihrer 60-jährigen Cousine Collette. Geschlossen ist das Lokal, abgesehen vom sonntäglichen Ruhetag, nur am 15. August, wenn in Daraoun Mariä Himmelfahrt gefeiert wird.

Charbel Bassil lebt mit seiner Familie im Dorf Daraoun, rund 16 Kilometer vor Beirut. In der schweren Krise des Landes klammert sich der 52-Jährige an seinen christlichen Glauben

An dieser Stelle muss wohl gesagt werden, was das „Le Chef“ neben seiner Küche ausmacht. „In diesem Restaurant herrscht radikale Gleichheit“, sagt Ronnie Chatah. Der 39-Jährige, der Pferdeschwanz und Henri-Quatre-Bart trägt, moderiert Libanons bekanntesten Podcast „The Beirut Banyan“, vor der Pandemie führte er auch Touristen durch die Stadt. „‚Le Chef‘ steht für mich für Gemmayzeh, das Essen dort ist simpel und gut“, sagt Chatah, „und Charbel schenkt allen die gleiche Aufmerksamkeit – jeder ist dort ein Star.“ Vielleicht fühlen sich deshalb im „Le Chef“ auch echte Berühmtheiten wohl. 2006 kam der US-Starkoch Anthony Bourdain mit der Crew seiner CNN-TV-Show „No Reservations“ in die Rue Gouraud.

„Dieser Ort hat sich sofort vertraut angefühlt, wie ein New Yorker Diner“, sagt der Amerikaner in der Folge, die noch immer online abrufbar ist. Man sieht, wie Bourdain Fladenbrot in Hummus und das Auberginenpüree Muttabal tunkt, dazu trinkt er Arak, libanesischen Anisschnaps auf Eis. Im Hintergrund bellt Charbel Bassil seine Bestellungen durch den Gastraum. „Die Atmosphäre war einfach gut, ich war dort glücklich“, resümierte Bourdain damals seinen Besuch. Die Episode zeigt, wie nah Genuss und Gefahr in Beirut beieinanderliegen: Am Tag nach Bourdains Besuch brach der Sommerkrieg zwischen Israel und der islamistischen Hisbollah-Miliz aus.

– Charbel Bassil

„All diese Menschen hier im Viertel

sind meine Nachbarn,

sie sind meine Familie“

An der gegenüberliegenden Fassade zeugen noch immer Einschusslöcher von dieser Zeit. „Doch eine Katastrophe wie die vom

4. August 2020 hat es nie zuvor gegeben“, sagt Charbel. Im Moment der großen Explosion, um kurz nach sechs Uhr abends, waren noch zwei Gäste im Restaurant. Paul war schon zu Hause, sein Bruder hatte sich gerade mit einem Teller Fisch an den Tresen gesetzt, auch Cousine Collette war noch im Restaurant. Dann krachte es zum ersten Mal. Im Hafen, nur 600 Meter vom „Le Chef“ entfernt, waren gelagerte Feuerwerkskörper detoniert, was 35 Sekunden später die verheerende Explosion des Ammoniumnitrats auslöste. Nach der zweiten Explosion schoss eine Druckwelle mit 2500 Metern pro Sekunde durch die Stadt.

Charbel wurde von einem Splitter der geborstenen Kühlschranktür im Nacken getroffen, außerdem an Ellenbogen und Unterschenkel verletzt. Schlimmer hatte es Ghazi Mabrouk erwischt, einen der syrischen Hilfsköche. Er lag ohnmächtig in der verwüsteten Küche. Wie durch ein Wunder war der 30 Jahre alte Volvo des Restaurants noch fahrtüchtig. Charbel brachte damit trotz des Chaos erst den Koch, dann eine Nachbarin und ihren Sohn und schließlich einen unbekannten Verletzten, der stark blutete, in verschiedene Krankenhäuser. Dann erst ließ er sich in einem Spital bei Dschounieh versorgen, der Hafenstadt nördlich von Beirut.

Mit der Mutter Gottes und Spenden aus Hollywood: Charbel Bassil ist es gelungen, das „Le Chef“ vorerst zu retten. Doch die Sorgen bleiben

Das „Le Chef“ lag in Trümmern. Türen und Fenster, Mobiliar, Herd und Kühlschränke, Wandverkleidungen, Klimaanlage und Kasse: alles zerstört. „Einen Monat lang haben wir nur aufgeräumt“, erinnert sich Paul. Schließlich berieten die Brüder und ihre Cousine über die Zukunft des „Le Chef“. Und beschlossen, dass es weitergehen muss. Aber wie? 15.000 Dollar würde die Renovierung sicher kosten. Geld, das sie nicht hatten. Dann bekam Charbel einen Anruf aus den USA: Die Filmemacherin Amanda Bailly, die jahrelang in Beirut gelebt hatte, wollte helfen. Mit Richard Hall, einem britischen Journalisten, startete sie die Crowdfunding-Aktion „Rebuild Le Chef“. Ab dem 12. August, also gut eine Woche nach der Explosion, gingen die ersten Spenden ein. Unter den ersten Gebern war ein gewisser Russell Crowe, der 5000 Dollar spendete. Hall fragte bei Twitter nach: Wirklich der @russellcrowe?

Der Hollywood-Star antwortete prompt: „Das war für Anthony Bourdain. Ich dachte, er hätte das selbst getan, wenn er noch da wäre.“ Bourdain beging 2018 Selbstmord. Insgesamt kamen 19.509 Dollar von 299 Spendern zusammen, weit mehr als von Bailly und Hall erhofft. Vier Monate nach der Explosion eröffnete das „Le Chef“ wieder.

Inmitten von Trauer und Trauma ist das „Le Chef“ heute für viele Beirutis ein Zeichen der Hoffnung. An der neuen Glasfront hängt ein Foto des „Gladiator“-Darstellers: „Thank You, Russell Crowe!“ Ein Happy End? „Geld verdienen wir keines mehr“, sagt Charbel, „wir arbeiten nur noch, um zu überleben“, ohne Schmerzmittel geht wenig.Aber ein Leben ohne „Le Chef“, wo das Kibbeh mit einer besonders krossen Kruste serviert wird? Für Charbel Bassil unvorstellbar. „Am glücklichsten bin ich, wenn das Restaurant voll ist. Dann fühle ich mich lebendig.“

- Thore Schröder

Beten, bangen, weitermachen: Charbel Bassil hält das Restaurant offen und das Geschäft am Laufen – inmitten einer halb zerstörten Stadt

MITWIRKENDE

THERESA BREUER

Theresa Breuer, 35, verliebte sich in den Nahen Osten, als sie 2009 mit ihrem VW-Bus von Berlin nach Beirut fuhr. Seitdem lebt und arbeitet die Filmemacherin und Autorin in der Region, viele Jahre davon im Libanon. In ihren Filmen und Reportagen erzählt sie die Geschichten der Menschen hinter den Schlagzeilen. In der Vergangenheit ist sie dafür mit Jugendlichen per Anhalter durch den Iran gefahren, hat syrische Flüchtlingskinder in die Schule begleitet und mit afghanischen Frauen den höchsten Berg Afghanistans bestiegen. Nach der Explosion 2020 kehrte sie nach Beirut zurück, an den Ort, der sie nie losgelassen hat.

THORE SCHRÖDER

Thore Schröder wurde 1982 in Hamburg geboren. Seit sechs Jahren arbeitet er als freier Journalist im Nahen Osten. Im Oktober 2019, wenige Tage vor Ausbruch des Volksaufstands im Libanon, zog er nach Beirut. Statt Reformen erlebte er vor Ort den Zusammenbruch der Wirtschaft und die Pandemie. Als am 4. August 2020 das Ammoniumnitrat in Hangar 12 des Hafens explodierte, war er zufällig im Süden des Landes – er fuhr sofort zurück nach Beirut. Noch am selben Abend interviewte Schröder zahlreiche Opfer und Helfer in den verwüsteten Stadtvierteln. In den Tagen darauf erlebte er viel Leid, aber auch den Zusammenhalt und die Tatkraft der Libanesen. „Wie die Menschen in Beirut mit dieser Katastrophe umgegangen sind, hat mich tief beeindruckt“, sagt Thore Schröder, „für mich ist diese Stadt in den Tagen nach der Explosion endgültig zu meinem Zuhause geworden.“

.jpg)

VANESSA SCHLESIER

Seit 2012 pendelt Vanessa Schlesier zwischen dem Nahen Osten und Berlin. Ihre Dokumentationen haben oft einen investigativen Ansatz, der die Geschichten hinter den News erzählen soll. Seit 2013 begleitet sie die syrische Flüchtlingsbewegung in all ihren Facetten, sie schrieb über den Krieg 2014 in Gaza und dokumentiert die Entwicklung des Libanon seit der Explosion. Vanessa Schlesier ist Stipendiatin der Quandt Foundation, erhielt das Memento-Stipendium und wurde 2014 vom Fachblatt „medium magazin“ auf die Liste von „Deutschlands Top-30-Journalisten unter 30“ gewählt.

MEIKO HERRMANN

Meiko Herrmann ist ein renommierter deutscher Fotograf. Er ist weltweit für diverse Magazine, Zeitungen, NGOs und Werbeagenturen tätig. Seine Arbeiten zeichnet ein humanistisches Bild in teils sehr sensiblen Momenten des Daseins aus. Ebenso findet man seine Fotografien in großen Reise- und Abenteuergeschichten aus den entferntesten Winkeln unseres Planeten. Er ist bereits mit wichtigen Preisen, darunter der World Press Photo Award, ausgezeichnet worden.

.jpg)

PIERRE JARAWAN

Pierre Jarawan wurde 1985 als Sohn eines libanesischen Vaters und einer deutschen Mutter in Amman, Jordanien, geboren, wohin seine Eltern vor dem Bürgerkrieg geflohen waren. 2012 wurde er Internationaler deutschsprachiger Meister im Poetry Slam. Sein Romandebüt „Am Ende bleiben die Zedern“, für das er zahlreiche Auszeichnungen erhielt, war ein Sensationserfolg und ist heute, übersetzt in viele Sprachen, ein internationaler Bestseller.